The Murky Underwater of Deep Sea Mining.

How Deep Sea Mining stands at the nexus of great power tension, national sovereignty, and the Anthropocene.

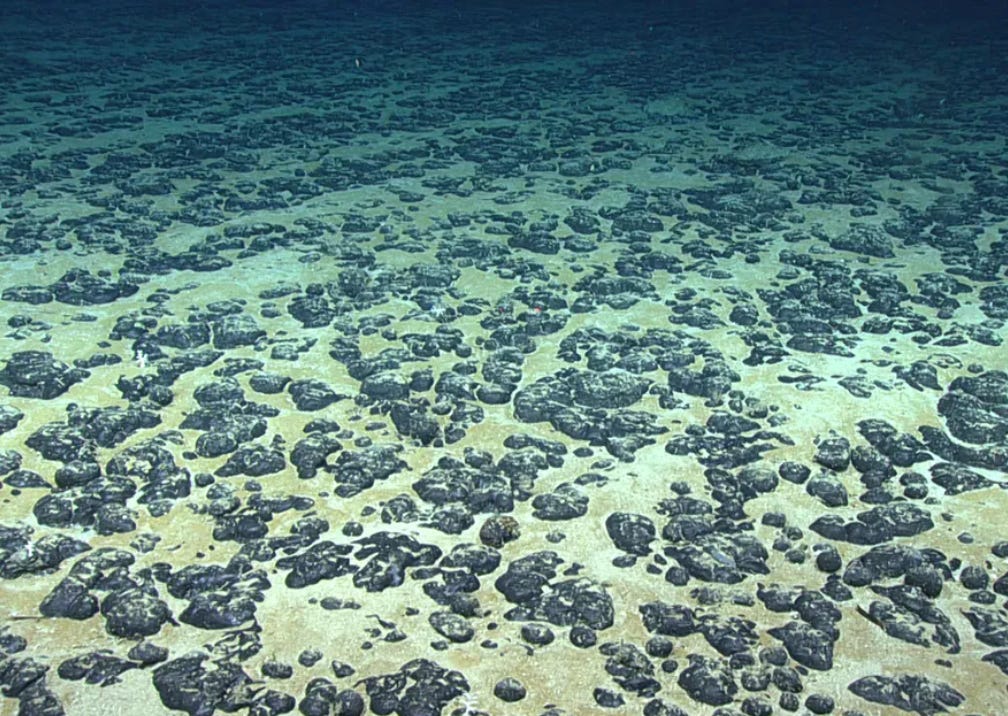

In April 2021, the Belgian company Global Sea Mineral Resources tested the collection of seabed nodules using a pre-prototype nodule collector, testing at a depth of 4500 metres. It was the first mining trial of its kind in the Central Pacific since the 1970s metal crunch, and represents a flared commercial interest in deep sea mining (DSM) amidst a mineral shortage, which has now been exacerbated during the Russia Ukraine War. DSM has various advantages, based around medical and commercial interests of exploration, supply and logistics. It is also key to the ‘security’ debate. For example, the UK government’s Resource Security Action Plan (2012) exemplifies this by emphasising the exploration of both new and old geographies, and predates the 2014 Deep Sea Mining Act which allows the government sponsorship with DSM contracts, whilst complying with the International Seabed Authority’s regulations. It frames DSM as the basis of security, which is essential in a rare earth element market dominated by China. The implication is that, as will be discussed, this extractive form of geopolitics has led to tensions between human political choice, and scientific discourse on the environmental damage caused by these choices. This article grasps this thesis by appealing to two strands. Firstly, I will discuss the legislative and political issues surrounding DSM in national contexts. Secondly, I will use environmental and scientific debates to reveal the tensions between governments and corporations as both political and earthly actors. DSM initiatives reveal the contestations between these various legislative, political and environmental concerns.

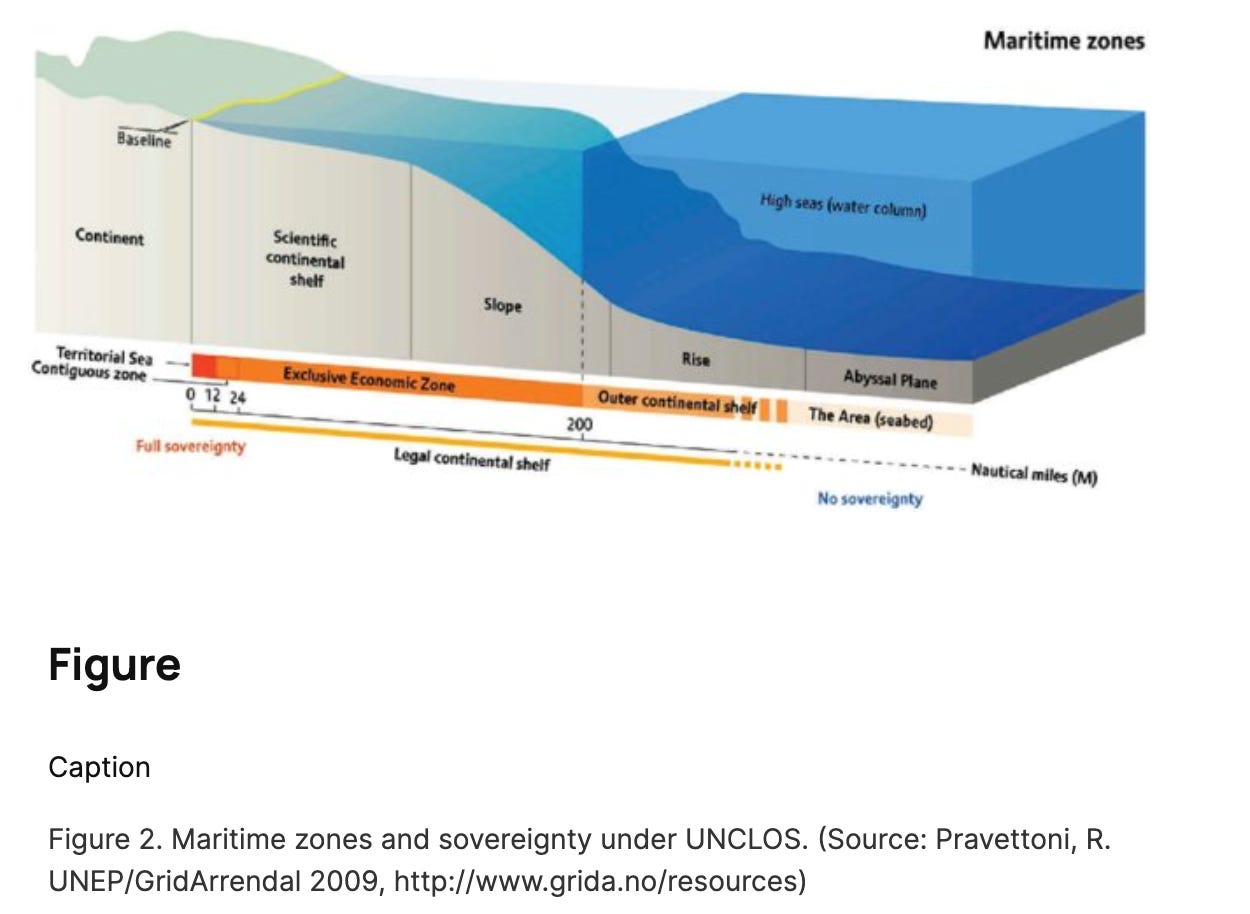

Legal tensions; UNCLOS, ISA, and the Freedom of the Seas

The United Nations Law of Seas Convention (UNCLOS) determines activity in the ocean space through regulation, beginning in 1982 through the establishment of a 200 nautical mile wide economic zone extending into the sea-bed. Yet criticisms of this clause appeared due to Article 136, which stated that ‘the Area (the subsoil and sea beyond national jurisdiction) and its resources (solid, liquid and gaseous minerals such as the polymetallic nodule) are the common heritage of mankind’. Importantly, this occurred before scientific developments such as marine bioprospecting and the commercial use of nodules, not including mineral extraction beyond national jurisdictions. This area covers 60% of the ocean bottom. In 1994 this led to the creation of the International SeaBed Authority, which targets this innovation. However, the issue is the lack of integration between the two regulatory bodies, and differing interpretations of the mining code. In 2021, the island of Nauru in the central pacific transitioned from exploration to exploitation of the ocean bottom. They were free to do by the terms of the draft regulations on exploitation of mineral resources in the Area (ISA) in 2019, where regulation 1.4 states that:

These regulations shall not in any way affect the freedom of scientific research, pursuant to article 87 of the Convention, or the right to conduct marine scientific research in the Area pursuant to articles 143 and 256 of the Convention. Nothing in these regulations shall be construed in such a way as to restrict the exercise by States of the freedom of the high seas as reflected in article 87 of the Convention. (UNCLOS, 1.4)

However, the ISA code which claims a 2 year period after a country starts mining to determine the legitimacy of its activity, has led to a recent recognition for the urgency for regulation. Nauru reveals a case of a country that abides by the ISA laws, but its exploitative activities on the sea-bed ‘Area’ beyond its jurisdiction, and the institutionally delayed response of the ISA, require scrutiny and reform. A similar case is shown by China, who holds 5/30 DSM contracts and has pursued multiple actions in the South China Sea. Its vague laws on DSM permits it to influence environmental norms, especially due to its financial contribution to the ISA. It has also established a joint DSM training and research centre in Qingdao, operated by the State Oceanic Administration. Chinese aims in the SCS are multifarious, including energy supplies, but also geopolitical aims. The 2019 National White Defence Paper reiterates that the SCS is ‘inherent territory’ in chinese defence. Therefore, DSM activity in the SCS may have ulterior motives which are not legally regulated by the vague terms of the ISA and the principle of the sea as a ‘common to all humanity’. China’s actions have also included genetic DSM, where undiscovered marine species may provide genetic therapy and biological defence mechanisms. The global market for marine biotechnology is projected to reach $6.4 billion by 2026. Whilst European companies such as German BASF have registered 47% of marine sequences in gene patients, China’s State Oceanic Administration announced a rapid expansion of its collection of deep sea microbes in 2017. A critical outlook on this mineral oceanic competition for resources and pharmaceutical innovation has already appeared in publications such as the United States Institute of Peace, which sees the insubstantiality of the UNCLOS/ISA, and the US’ own non-membership in UNCLOS, as a threat to the bio-political and energy sphere. There must be fast-acting guidelines on mineral exploitation, combined with legal oversight on specific actors’ intentions and how the Area is defined in relation to national claims to oceanic regions beyond jurisdictions.

Scientific pushback

DSM represents a conflict between the Anthropocene and environmental concerns. More than 600 scientists and policy experts signed a petition in February 2022, calling to pause private and governmental DSM initiatives. These concerns have long-lasting foundations. In 1989, a German scientist Hjalmar Theil led a DSM test, funded by the ministry of Science and Technology, in the coast of Peru, which included an 8-metre wide plough through the seafloor. 26 years later, scientists and ecologists from the National Oceanography Center in the UK found clouds of sediment in the same site which had travelled 409 kilometres. Pushback against global DSM projects have come from multiple sources, ranging from scientists to international bodies who have called for a 10 year moratorium on deep-sea exploration. In May 2020, the European Commission stated that precautionary principles on the associated risks of DSM must be considered before any deep sea exploration, and this was followed by 81% of States and 95% of NGOs supporting a moratorium and reform of the ISA in the September 2021 International Union for the Conservation of Nature World Conservation Congress.

Yet, there are still Issue Briefs published on the need for DSM for national security and the supply of minerals, particularly in regions such as the Hague. There are a number of leading Dutch companies who see DSM as an opportunity for the Dutch industry to become a leader and knowledge supplier to other nations. Seafloor mining companies such as Minerals Transfer (Rotterdam) and Offshore Operations, are at the forefront of dredging exploration technologies, critical to a nation which has little to no access to raw materials. What is required is implementing legislation that will allow regions such as the Netherlands to conduct influence in international mineral technologies, whilst developing ecologically sound practices that are in line with scientific assertions on oceanic protection.

Overall, DSM is a dependent variable on which various factors such as great-power tension, national sovereignty and medical advancement hinge. The uneven establishment of legislation in the UN bodies provides loopholes for companies to gain monopolies on the ocean floor beyond their national jurisdiction to fulfil ulterior motives. Yet there is also the concrete scientific pushback against initiatives, which must withstand national aims of access to raw minerals, and the principle of Freedom of the Seas. I believe the urge for a moratorium is the correct action, but must involve the input of political, scientific and diplomatic bodies to ensure that national security is not favoured at the expense of the stability of the ecosystem.

References:

Jocelyn Trainer (November 3 2022) “The geopolitics of deep sea mining and green technologies” United States Institute of Peace https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/11/geopolitics-deep-sea-mining-and-green-technologies

John Childs (2020) Extraction in Four Dimensions: Time, Space and the Emerging Geo(-)politics of Deep-Sea Mining, Geopolitics, 25:1, 189-213 DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2018.1465041

Houses of Parliament (2015) ‘POST NOTE: Deep Sea Mining’ http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/POST-PN-0508

House of Lords (1 March 2022) UNCLOS: The law of the sea in the 21st century, International Relations and Defence Committee https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/9005/documents/159002/default/

Pradeep Singh (December 2021) “The two-year deadline to complete the International Seabed Authority’s Mining Code: Key outstanding matters that still need to be resolved” Marine Policy 134 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X21004152

IUCN (May 2022) “Deep Sea Mining” Issues Brief. https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/deep-sea-mining

Will Hylton (February 2020) “Deep sea mining and the race to the bottom of the ocean” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/01/20000-feet-under-the-sea/603040/

United Nations University- Institute of Advanced Studies (May 2005) “Bioprospecting of Genetic Resources in the Deep Seabed: Scientific, Legal and Policy Aspects” https://www.cbd.int/financial/bensharing/g-absseabed.pdf